19. Wave loads#

List of symbols:

\(\begin{array}{ll}c &= \text { phase velocity} ( c=\omega / k) \\ d &= \text { water depth} \\ d_{c} &= \text { thickness of protection block layer} \\ f &= \text { frequency} (=1/T) \\ f_{p} &= \text { frequency corresponding to} T_{p} \\ g &= \text { acceleration of gravity} \\ h &= \text { water depth in front of the structure;} \\ h^{\prime} &= \text { water depth at the toe of the front wall} (= d+d_{c} )\\ h_{b} &= \text { water depth at a distance of 5 times the significant wave height}\\ k &= \text { wave number} ( k=1 / \lambda) \\ u(x, z, t) &= \text { horizontal particle velocity}\\ \dot{u}(x, z, t) &= \text { acceleration} \\ u &= \text { water velocity perpendicular to structural member} \\ \dot{u} &= \text { water acceleration perpendicular to structural member} \\ u-\dot{x} &= \text { relative velocity} \\ \dot{x} &= \text { cylinder velocity} \\ \ddot{x} &= \text { cylinder acceleration} \\ x, y, z &= \text { coordinates} \\ A &= \text { cross section area} \\ A_{\gamma} &= \text { normalisation factor,} \approx 1-0.287 \ln (\gamma) \\ C_{M} &= \text { inertia coefficient} \\ C_{D} \cdot &= \text { drag coefficient} \\ D &= \text { cylinder diameter} \\ F &= \text { force per cylinder length in flow and motion direction} \\ H_{s} &= \text { significant wave height} \\ H &= \text { incident wave height (from trough to crest) in front of the structure} \\ K &= \text { non-linearity factor} \\ L &= \text { wave length;} \\ M_{n} &= \text { n-th (spectral) moment} \\ S &= \text { significant wave slope} \\ S(f), S(\omega) &= \text { spectral density} \\ T &= \text { wave period.} \\ T_{p} &= \text { peak period} \\ T_{z} &= \text { mean wave period} \\ T_{m o 2} &= \text { average wave period} \\ T_{d} &= \text { duration of sea state}\\ T(z, \omega) &= \text { transfer function} \\ V &= \text { coefficient of variation} \\ \alpha &= \text { generalised Phillips' constant, scale parameter} \\ \alpha_{1}, \alpha_{2}, \alpha_{3} &= \text { factors dependent on hydraulic conditions (see {eq}`eq-wave-2-56`)} \\ \alpha_{4} &= \text { kurtosis} \\ \beta &= \text { shape parameter} \\ \beta &= \text { angle of wave incidence} \\ \gamma &= \text { location parameter} \\ \gamma &= \text { peakness parameter in spectrum} \\ \delta, \varepsilon &= \text { spectral width} \\ \phi_{s} &= \text { mean wave direction} \\ \lambda &= \text { wave length} \\ \lambda_{1}, \lambda_{2}, \lambda_{3} &= \text { factors in wave force model} \\ \theta &= \text { wave direction} \\ \theta_{w} &= \text { wave model unertainty} \\ \theta &= \text { angle between the elementary wave and the main wave direction} \\ \theta_{\mathrm{MG}} &= \text { model uncertainty marine growth} \\ \eta(x, y, t) &= \text { surface elevation} \\ \nu_{0}^{u} &= \text { zero-crossing frequency} \\ \tilde{\nu}(z) &= \text { ensemble averaged up-crossing rate} \\ \rho &= \text { density of water} \\ \rho_{i j} &= \text { coefficient of correlation between members} \\ \sigma &= \text { standard deviation, spectral width parameter} \\ \tau &= \text { short-term duration} \\ \omega &= \text { angular wave frequency} (=2 \pi f) \\ \omega_{p} &= \text { angular spectral peak frequency} (= 2 \pi f_{\mathrm{p.}})\\ \vec{\psi} &= \text { environmental state}\end{array}\)

19.1. Introduction#

Waves as relating to wave loads on structures are usually described in terms of sea states. A sea state is an approximately stationary condition described by parameters with long-term fluctuations. These parameters include the significant wave height \(H_{s}\), the mean wave period \(T_{z}\), the peak period \(T_{p}\) and the wave direction \(\theta\).

The waves in a sea state are usually described by means of the statistics of the surface elevation \(eta(x, y, t)\). Wave forces depend on the velocity and acceleration of water particles below the surface. The relation between these variables can be found using wave theories. Among these may be mentioned:

Linear wave theory, by which the wave profile is described as a sine function.

Solitary wave theories for particularly shallow water.

Cnoidal wave theories which cover the waves above as special cases.

Stokes wave theories for particularly high waves

Stream-function waves, which are based on numerical methods and accurately, describe the wave kinematics over a broad range of water depths

Solitons, weakly non-linear dispersive waves

Wave packets, solutions of Non-Linear Schroedinger Equation

The following wave theories are in common use ( \(d\) is the water depth and \(\lambda\) is the wave length):

Solitary wave theory for \(d / \lambda<0.1\);

Stokes’ \(5^{\text {th }}\) order theory for \(0.1<d / \lambda<0.3\);

Linear wave theory for \(d / \lambda>0.3\).

For most practical purposes an appropriate order of Dean’s Stream Function or Stokes’ 5th is applicable for regular wave analysis. For the spectral description of random seas, the linear wave theory is almost always used.

The most important solution of the linear wave equations is the long crested wave. The surface elevation is a sine wave with amplitude \(a\) progressing with phase velocity \(c=\omega / k\),

if the wave direction is parallel to the \(x\)-axis. More general wave forms can be generated by superposition of plane waves with different values of \(a\) and \(\omega\). The dispersion relation between wave number \(k=1 / \lambda\) and angular wave frequency \(\omega\) reads

Here \(g\) is the constant of gravity and \(d\) is the water depth. The deep water approximation \(\omega^{2}=g k\) is valid for depths exceeding approximately half the wavelength.

The horizontal particle velocity \(u(x, z, t)\) and acceleration \(\dot{u}(x, z, t)\) follow from:

where \(T(z, \omega)\) is a transfer function.

For large \(\omega\), the dispersion relation degenerates into the deep-water form, and

The limiting average wave steepness for short-term irregular seastates may in absence of other reliable sources be taken as:

and interpolated linearly between the boundaries.

Stretching of wave theory to the instantaneous sea surface should be performed. When linear wave theory is applied, the extrapolation of the wave kinematics to the free surface is most appropriately carried out by substituting the true elevation, at which the kinematics are required, with one which is at the same proportion of the still water depth as the true elevation is of the instantaneous water depth. This can be expressed as follows

where:

\(z_{s}=\) The modified coordinate to be used in particle velocity formulation

\(z=\) The elevation at which the kinematics are required (coordinate measured vertically upward from the still water surface)

\(\eta=\) The instantaneous water level (same axis system as z)

\(d=\) The still, or undisturbed water depth (positive).

This method ensures that the kinematics at the surface are always evaluated from the linear wave theory expressions as if they were at the still water level [19.01].

19.2. The short-term random wave process#

19.2.1. Wave spectrum and sea state parameters#

During a relatively short period, waves can be conceived as a superposition of deterministic wave components with random phase and amplitude. As a result the waves form a stationary Gaussian process. The period for which such a model holds is called a sea state. The process is described by a variance spectrum \(S_{\eta \eta}(\omega)\). Before introducing this spectrum in more detail it is convenient to introduce the spectral moments.

19.2.2. Spectral Moments#

The spectral moment \(M_{n}\) of general order \(n\) is defined as

where \(\mathrm{n}=-1,0,1,2,\ldots\)

Quantities that may be defined in terms of spectral moments are among others:

Significant wave height

where \(\sigma_{\eta}\) is the standard deviation of \(\eta(t)\).

Average wave period

Significant wave slope

Spectral width

If the spectral density is given as a function of the frequency \(f, S=S(f)\), the relation is

Similarly, if the moments of the circular frequency spectrum \(S(f)\) are denoted \(M_{n}(f)\), the relationship to \(M_{n}\) is

Note: If the period is not given for a particular sea-state, a tentative estimate

where \(T_{z}\) is in seconds and \(H_{s}\) is in metres.

19.2.3. Single peak spectrum#

The most frequently used spectra are the JONSWAP (Hasselman et al., 1973) spectrum and the [19.02]. Both spectra describe wind sea conditions that are reasonable for the most severe seastates.

The originally proposed PM spectrum is:

where \(g\) is the acceleration of gravity, and \(\omega_{p}\) is the angular spectral peak frequency.

The [19.03] version of the PM spectrum is

The PM spectrum is meant to be applied for fully developed seas. Observations indicate that the empirical spectrum is often more peaked than the PM spectrum. The JONSWAP spectral density function is:

where

\( \omega =\text { Angular wave frequency, } \omega=2 \pi f \)

\(f =\text { Wave frequency, } f=1 / T\)

\(T =\text { Wave period. }\)

\(T_{p} =\text { Peak period }\)

\(f_{p} =1 / T_{p}\)

\(\omega_{p} =\text { Angular spectral peak frequency } \omega_{p}=2 \pi f_{p}\)

\(g =\text { Acceleration of gravity. }\)

\(\alpha =\text { Generalised Phillips’ constant, } =(5 / 16)^{*}\left(H_{s}{ }^{2} \omega_{p}{ }^{4} / g^{2}\right)^{*} ~A_{\gamma}\)

\(A_{\gamma} =\text { Normalisation factor, } \approx 1-0.287 \ln (\gamma)\)

\(\sigma =\text { Spectral width parameter. } =0.07 \text { if } \omega \leq \omega_{p}\)

\(\sigma = \text{Spectral width parameter} = \begin{cases} 0.07 & \text{if } \omega \leq \omega_p \\ 0.09 & \text{if } \omega > \omega_p \end{cases}\)

\(\gamma =\text { Peakness parameter }(\gamma=1.0 \text { for PM })\)

If no particular values are given for the peakedness parameter \(\gamma\), the following value may be used:

where \(T_{p}\) is in seconds and \(H_{s}\) is in metres.

For the JONSWAP spectrum the spectral moments are given approximately as

The average zero-crossing wave period \(T_{z}\) may be related to the peak period \(T_{p}\) by

Note: A possible non-conservatism related to the choice of the spectral model is due to the definition of the frequency exponent describing the equilibrium range of the spectrum. The JONSWAP and Pierson-Moskowitz spectra adopt \(\omega^{-5}\). Both the theory, as well as recent analysis of spectral data [19.04], show that the tail of the JONSWAP spectrum is indeed closer to \(\omega^{-4}\), as has already been noted by [19.05]. The tail behaviour may be important for structural response. E.g., [19.06] show that the \(f^{-4}\) assumption may increase the dynamic response of a jacket structure by \(25 \%\) as compared to the \(f^{-5}\) model.

19.2.4. Double peak spectrum#

Moderate and low sea states in open sea areas, are often composed of both wind sea and swell (e.g. the Western coast of Europe). A two-peak spectrum may be used to account for combined sea states, i.e.

Splitting of the wave spectrum into wind sea and swell have been made by several authors ([19.07]; [19.08]; [19.09])

Ochi and Hubble represent each spectrum component by a three parameter formula of a Gamma type. The parameters should be determined numerically to best fit the observed spectra.

Input parameters to the Torsethaugen spectrum are significant wave height and peak period. A modified JONSWAP spectrum is used for both wind sea and swell peaks, and the spectrum parameters are related to \(H_{s}\) and \(T_{p}\) according to empirical parameters based on analysis of measured data from the Norwegian and North Sea.

19.2.5. Directional wave spectrum#

Directional short-crested wave spectra \(S(\omega, \theta)\) may be expressed in terms of the nondirectional wave spectra,

where the latter equality represents a simplification often used in practice. Here \(D(\theta, \omega) ; D(\theta)\) is a directionality function, and \(\theta\) is the angle between the direction of elementary wave trains and the main wave direction of the short crested wave system.

The directionality function fulfils the requirement

Different forms of directional functions are given in the literature. An early formulation is the cosine-power model

Due consideration is to be taken to reflect an accurate correlation between the actual sea-state and the constant, \(`n\). The main direction may be set equal to the prevailing wind direction if directional measurements are not available.

A commonly applied cosine-power form is the cos-2s distribution introduced by [19.010]

Measurements should indicate which form and parameters should be preferred.

19.2.6. Crest distribution for Gaussian Sea-State#

The statistical distribution of individual wave crests \(Z\) in an irregular short-term stationary sea state is in a linear, narrow band approximation the same as the distribution of the envelope of a Gaussian process, i.e. the Rayleigh distribution

where \(\sigma_{\eta}=H_{s} / 4\). The extreme value distribution \(F_{E}(z)\) of crest in a stationary sea state of duration \(\tau\) follows by assuming Poisson upcrossings of level \(z\) as

19.2.7. Crest distribution for Non-Gaussian Sea-State#

The Gaussian model fails to capture asymmetric, non-linear wave aspects caused by dynamic pressures not included in the linear theory, which is essential for shallow water, but can also be important for deep-water applications. A possible classification of statistical procedures for assessment of non-Gaussian processes \(\eta(t)\) is

establish the probability distribution of the elevation process \(\eta(t)\) by modification of a simpler distribution, usually the Gaussian distribution

transform the elevation process \(\eta(t)\) into a Gaussian process \(U(t)\) and apply properties of the Gaussian process

establish the exact joint distribution function of the process and the differentiated process

fit a distribution function to the sample of local peaks.

19.2.8. Distribution for wave heights#

Assuming a Gaussian narrow banded sea surface elevation, the individual wave heights are described by the Rayleigh distribution as shown by [19.011], and [19.012]

For not too narrow banded waves this distribution is a good approximation only when the root-mean-square (rms) amplitude is used instead of the sea surface elevation standard deviation, [19.013].

Other studies of the probability distribution of wave heights are made by e.g. [19.014], [19.05], [19.015], [19.016]. The following expression for the exceedance probability for high \(h\) values is due to [19.017], [19.018]

where \(k\) is a parameter for the correlation between crest and subsequent trough.

The extreme wave height estimates can be transformed into measures for the crests using e.g. Stokes theory or regression analysis. E.g., [19.019] analyse data from the Central North Sea (Gorm field) and finds the expected ratio 0.69 between extreme crest height and extreme wave height.

Note that wave heights may be correlated to water levels through the wind speed.

19.3. Long-term wave conditions#

19.3.1. Marginal distribution of significant wave height#

Long-term variations of sea states characteristics represent a base for establishing metocean criteria for design of offshore structures and for different operational conditions. The long-term description of waves is usually governed by the variation of significant wave height.

The following analysis strategies are commonly applied:

Global method, in which all regular data (all 3-hour data) are fitted by an appropriate distribution function, for example a 3-parameter Weibull distribution.

Peak over threshold method or storm analysis method, in which peaks over specified thresholds are identified and fitted by a set of relevant statistical distributions (Gumbel, Weibull, exponential). Sensitivity analysis with respect to threshold level should be performed.

Annual extremes, in which annual or seasonal extremes are fitted by relevant extreme value distributions.

In selecting the method there is a tradeoff between the global models using all data and the extreme event models based on a subset of the largest data points. While the global approach utilises more data, it can obscure critical tail behaviour and introduce correlation between observations. In contrast, extreme events may be more nearly independent, but their scarceness increases statistical uncertainty. Effect of uncertainty is discussed in more detail in Chapter 19.6..

Frequently applied distribution functions for marginal distribution of significant wave height are for global data 2-parameter Weibull, 3-parameter Weibull and a hybrid lognormal plus 2-parameter Weibull distribution. For event models, 3-parameter Weibull, Gumbel and Generalized Pareto (for Peak Over Threshold) are commonly used. Local measurements should give indications which distribution type is to be preferred.

The 3-parameter Weibull distribution for variable \(X\) is given as

where \(\alpha=\) scale parameter, \(\beta=\) shape parameter, \(\gamma=\) location parameter.

The Gumbel extreme value distribution is

where \(\beta\) is a location parameter and \(\alpha\) is a scale parameter.

The Pareto distribution ( \(y=\) threshold excess values) is

Following [19.020], efficient parameter estimation is obtained by taking \(c=0\). This means that the data are exponential distributed

and that the extreme value distribution is of the Gumbel type.

19.3.2. Joint distribution of wave height and period#

Joint environmental models may often be used to approximate long-term variations of wave characteristics.

The existing joint environmental models are established by fitting distributions to data from the actual area. The Maximum Likelihood Model (MLM), [19.021], and the Conditional Modelling Approach (CMA), e.g. [19.06], utilize the complete probabilistic information obtained from simultaneous observations of the environmental variables. If the available information about the simultaneously occurring variables is limited to the marginal distributions and the mutual correlation, then the Nataf model can be used [19.022].

In the CMA, the joint density function is defined in terms of a marginal distribution and a series of conditional density functions modelled by parametric functions that are fitted to the conditioned data by some estimation procedure.

For a given directional sector the joint model of significant wave height and spectral/zero-crossing wave period is usually approximated by a marginal distribution for significant wave height, typically the 3-parameter Weibull distribution, and the conditional lognormal distribution for spectral/zero-crossing wave period given the significant wave height

where a possible parameterisation is

The parameters \(a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, b_{1}, b_{2}\) and \(b_{3}\) are determined from the data.

19.4. Extreme individual wave height and crest height#

The extreme individual crest or wave height can be determined by combining short term and long term statistics. The long-term distribution of waves is obtained by combining the joint long-term distribution of sea state parameters, with the short-term distribution of sea surface elevation. Let the short term, extreme value distribution of crest \(Z\) in an environmental state \(\vec{\psi}\) for a short-term duration \(\tau\) be denoted \(F_{Z \mid \vec{\psi}}(z \mid \vec{\psi} ; \tau)\). Conditioning on the environmental state \(\vec{\psi}\) may be integrated out, according to the theorem of total probability, to provide the corresponding short term, extreme value distribution for a single, random, environmental state. The extreme value distribution during an operation time \(\lambda\) might then be obtained as

where \(f_{\vec{\psi}}(\vec{\psi})\) is the probability density of the sea state parameters (e.g. \(h_{s}\) ).

This expression is based on the multiplication rule and an assumption of independence between the crest level in each short-term state. A slightly different formulation is the following expression due to [19.05]

where \(\tilde{v}(z)\) is the ensemble averaged up-crossing rate

Here \(v(z \mid \vec{\psi})\) is the mean upcrossing rate of the underlying process through the level \(z\), and \(F_{z \mid \vec{\Psi}}(z \mid \vec{\psi})\) is the distribution of the random cycle amplitudes. Note the difference between the integrands in Eq. (19.38) and Eq. (19.39), where \(F_{Z \mid \vec{\psi}}(z \mid \vec{\psi} ; \tau)\) is the short term extreme value distribution, while \(F_{z \mid \vec{\Psi}}(z \mid \vec{\psi})\) is the distribution of a random cycle amplitude.

As an alternative, an ensemble-averaged up-crossing approach may be used, in which the distribution function is expressed as [19.023]

Eqs. (19.38) to (19.41) may be applied directly in a Level 3 structural reliability analysis for modelling of the extreme crest. If the purpose is to estimate the 100 -year crest level, this quantity can be determined as the appropriate fractile of \(F_{E}(z ; \lambda)\).

In applications not the extreme wave height as such may be important, but rather the maximum load effect in the structure, e.g. the bending moment in a member. In this respect reference is made to [19.024].

19.5. Wave load models#

19.5.1. Slender members#

If the diameter of structural elements is small compared to a characteristic wavelength, the loads are calculated by the Morison formula

where

\(F =\) force per cylinder length in flow and motion direction

\(A =\pi D^{2} / 4\), cross section area

\(D=\) cylinder diameter

\(\dot{x}=\) cylinder velocity

\(\ddot{x}=\) cylinder acceleration

\(u=\) water velocity perpendicular to structural member

\(\dot{u}=\) water acceleration perpendicular to structural member

\(u-\dot{x}=\) relative velocity

\(C_{M}=\) inertia coefficient

\(C_{D}=\) drag coefficient

\(\rho=\) water mass density

For \(u>>\dot{x}\), a useful approximation is

The second term provides additional damping, and if the coefficient to \(\dot{x}\) is replaced by its expectation, the following form is obtained:

where \(\sigma_{u}\) represents the standard deviation of \(u\) in a random sea.

Another linearisation schemes exist that include the effect of combined wave and current. The scheme should depend on the application (e.g. collapse versus fatigue analysis).

Assume in the following that linear wave theory can be applied and that the wave elevation \(\eta(x, t)\) is a stationary Gaussian process. Then the particle velocity \(u(t)\) and acceleration \(\dot{u}(t)\) are also normal processes The relevant wave components \(u(t)\) and \(\dot{u}(t)\) then maybe considered as independent, zero-mean normal processes with standard deviations \(\sigma_{u}\) and \(\sigma_{\dot{u}}\). A measure of the relative importance of drag and inertia, and of the deviation from normal distribution, is

where \(k_{D}=\frac{1}{2} \rho D C_{D}\) and \(k_{M}=\rho A C_{M}\). In normalised form, the Morison can be expressed as the non-Gaussian process [19.025]

where \(X_{u}(t)=u(t) / \sigma_{u}\) and \(X_{\dot{u}}(t)=\dot{u}(t) / \sigma_{\dot{u}}\). The current velocity, inline with the waves, is \(V \sigma_{u}\). The natural period of variation of the current is assumed to be so long that its time variation can be ignored for the considered time span, hence \(V\) is taken as a fixed variable.

The second order statistics is characterised by the covariance matrix \(C_{\vec{X}}\) of the process

where \(\omega_{0} \equiv \sigma_{\dot{u}} / \sigma_{u}\) and \(\alpha\) is a bandwidth parameter for the velocity process u(t), i.e. \(\alpha=-\sigma_{\dot{u}}^{2} \sigma_{u}^{-1} \sigma_{i i}^{-1}\).

The mean \(\mu_{q}\) and standard deviations \(\sigma_{q}\) and \(\sigma_{\dot{q}}\) of the Morison force are given as [19.025]:

Let in the following \(V=0\). The probability density of the wave force \(Q(t)\) is completely determined by the non-linearity factor \(K\) and the variance of the force \(\sigma_{q}{ }^{2}\). The kurtosis \(\alpha_{4}\) gives the shape of the distribution of \(Q(t)\) through the relation

For the narrow band approximation \(\alpha \rightarrow 1\), the asymptotic result for the upcrossing rate is [19.025]

where \(v_{0}^{u}\) is the zero-crossing frequency of \(u(t)\). In a narrow-band approximation of the force, the distribution of local maxima can be obtained by neglecting the positive minima and negative maxima. This gives the probability density function of local maxima

and the asymptotic result

This density is derived in [19.026].

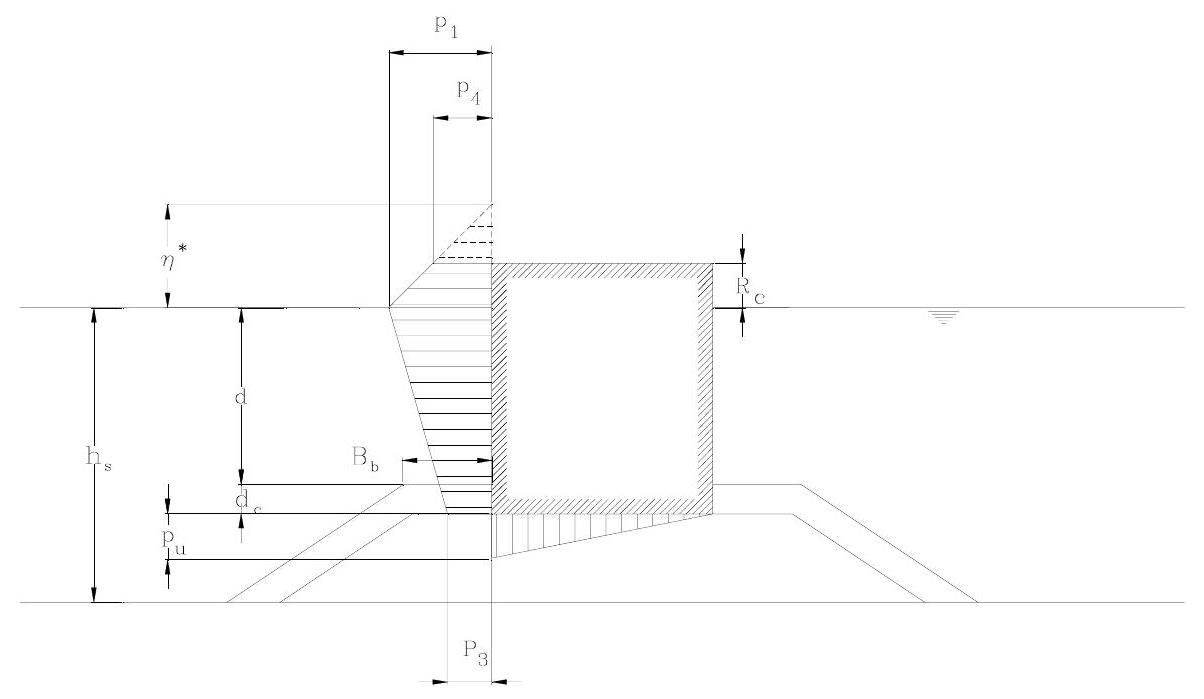

19.5.2. Vertical walls#

The water pressures \(p_{1}\) and \(p_{3}\) (see Fig. 19.1) on a vertical wall due to pulsating forces (impact and breaking excluded) are given by according [19.027]:

where:

\(H: \) incident wave height (from trough to crest) in front of the structure;

\(\beta: \) angle of wave incidence with respect to a line perpendicular to the structure;

\(\rho:\) density of water;

\(g:\) acceleration of gravity;

\(\alpha_{1}, \alpha_{2}, \alpha_{3}:\) factors dependent on hydraulic conditions (see (19.56))

\(\lambda_{1}, \lambda_{2}, \lambda_{3}:\) factors dependent on the structural geometry (usually =1.0)

The pressure at the top \(p_{4}\) for a given value of \(R_{C}\) can be derived from:

Fig. 19.1 Vertical wall on toe-structure#

The \(\alpha\)-factors are given by:

where

\(L:\) wave length;

\(h^{\prime}:\) water depth at the toe of the front wall \(=\left(d+d_{c}\right)\)

\(h:\) water depth in front of the structure;

\(h_{b}:\) water depth at a distance of 5 times the significant wave height.

\(d:\) water depth at top of protection blocks

\(d_{c}:\) thickness of protection block layer

19.5.3. Volume members#

For large-volume structures (i.e., structures for which a characteristic diameter is comparable to the wavelength), the hydrodynamic loads have to be determined by means of diffraction theory. An overview of the existing diffraction methods is given in ISSC (1991,2000). The diffraction theory is based on potential theory and viscous effects are neglected.

Usually, a linear diffraction analysis will have a sufficient accuracy, such that the load process becomes a linear function of the wave process. Non-linear diffraction theory should be used for shallow water structures, for structures situated in arctic areas with the presence of ice, for structures for which slow drift effects are important, and for calculation of springing response of a TLP. Forces in the splash zone are not adequately described by linear waves. This effect may, however, be accounted for by various stretching techniques without adhering to the full non-linear theory.

The second order hydrodynamic load effects may in many cases be important for the design of large volume structures. These effects may be:

When a linear regular first order wave is interacting with itself and an ocean platform.

For irregular sea the resulting second order exciting forces contain three components: the mean forces (drift forces), forces varying in time with the difference frequencies of the wave spectrum (often called slow drift forces) and with the sum frequencies of the wave spectrum (high frequency forces).

The difference frequency forces may in particular be important for design of mooring and dynamic positioning of offshore structures as well as for offshore loading systems.

A variety of perturbation-based frequency and time domain methods are presented in the literature

Superposing \(N\) waves with amplitudes \(a_{j}\), frequency \(\omega_{j}\) and phase \(\varepsilon_{j}, j=1, \ldots, N\)

the force (to second order) can be expressed as

where

where \(F^{(1)}\) is the linear transfer function (LTF) and \(F_{+}^{(2)}, F_{-}^{(2)}\) are sum- and differencefrequency force quadratic transfer functions (QTF). Response transfer functions, \(H^{(1)}, H_{+}^{(2)}, H_{-}^{(2)}\), corresponding to the force transfer functions, are found by solving the simultaneous linear equations of structural motions in 6 degrees of freedom.

Response quantities of interest include both extreme values and fatigue damage. In the following a simplified statistics in terms of four statistical moments is given.

The response \(x(t)\) is expressed in terms of standard normal processes \(u_{i}(t)\) that are independent at fixed \(t\) :

The coefficients \(\lambda_{i}\) are eigen values of the integral equation [19.028]

in which \(\Gamma\left(\omega_{1}, \omega_{2}\right)=H_{+}^{(2)}\left(\omega_{1},-\omega_{2}\right) \sqrt{S\left(\left|\omega_{1}\right|\right) S\left(\left|\omega_{2}\right|\right)} / 2\). The first order coefficient is next determined as

The moments follow by algebra as

E.g., by a Hermite transformation, these moments can be used to model the nonGaussian response process [19.029].

The Gaussian model is approached either if the \(\lambda_{i}{ }^{\prime} s\) become small relative to the \(c_{i}{ }^{\prime} s\), or when the number of significant \(\lambda_{i}\) terms grows.

This second order model has been used also for the slow drift problem (see e.g. [19.023], [19.030]).

19.5.4. Slamming loads#

Slamming loads in platform decks are important design consideration. Because of non-linear diffraction effects there is still no reliable method for assessing the loads.

In simplified 2D cases a generalised Wagner solution seems to describe the water entry loads. The water exit loads are, however, not properly described.

Impact forces associated with a slam induced whipping response can be reasonably predicted by 2D and 3D methods. However, some of the rigorous treatments that are available are CPU time consuming.

For ships with non-vertical hull-sides in high waves, slamming loads are important. The dominating force is the added mass force. A state-of-the-art review of studies on slamming, including theories, numerical methods, elastic responses due to impact loads and stochastic modelling, is given by [19.031].

Ship hull vibrations are often due to propeller cavitation.

19.6. Uncertainties#

Models for random variables

Table 19.1 presents a list of variables that could be considered as uncertain within a probabilistic wave load analysis. For every variable suggestions are presented for the probabilistic modelling. In most cases these suggestions are based on what is presented in the literature by various authors, sometimes on the basis of observations and data, sometimes only for use in example calculations. As a result, the background of the values given may differ substantially from one random variable to another.

In Table 19.1 mean values are often presented as to the nominal value or the locally measured value. The scatter, introduced as a coefficient of \(V\), may also depend heavily on local circumstances. The designation of the distribution type, is clarified at the bottom of the table. For variables which are defined per member or per joint, the value of \(\rho_{i j}\) indicates the coefficient of correlation between members. For the interpretation of \(\rho_{i j}\) it is convenient to have the following relationship:

\(V_{int}=\) member to member variability

\(V=\) total uncertainty

As an example, let the member to member variability for the yield stress within one structure be equal to \(V_{\text {int }}=0.4\). The total uncertainty is about \(V=0.8\). So:

In many practical calculations, values close to 0.0 or 1.0 should be rounded off.

In cases where little data is available, statistical parameters suffer seriously from “statistical uncertainty”. The most important statistical uncertainty concerns the uncertainty in the mean, which can be translated into an increased coefficient of variation. The coefficients of variation given in the Table should be considered as including this statistical uncertainty.

Some detailed comments to Table 19.1

Waves

The most important load parameter is the sea elevation \(\eta\), which can be considered as a zero mean piece-wise stationary Gaussion process. The parameters describing the spectra depend on the site location. When elaborating the parameters for a special case, however, it is recommended that one should take into account the statistical uncertainty due to the limited number of data, the effect of measurement errors and the difference in location between the measurement site and the construction site.

\(\boldsymbol{X}\) |

Designation |

\(\mu\) |

\(\mathbf{V}\) |

Dist type |

\(\rho_{i j}\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Measurement \(H_{s}\) |

nom |

0.10 |

- |

- |

|

\(H_{s}\) |

Significant wave height |

Local |

Local |

\(W/L\) |

- |

\(T_{z} \mid H_{s}\) |

Mean period for given \(H_{s}\) |

Local |

Local |

\(L/N\) |

- |

\(\phi_{s}\) |

Mean wave direction |

Local |

Local |

Local |

- |

\(T_{d}\) |

Duration of sea state |

3-6 hrs |

1.0 |

\(E\) |

- |

\(H_{\max } \mid H_{s}\) |

Max wave in given sea state |

Calculation |

Local |

\(G\) |

- |

\(\theta_{w}\) |

Wave model |

Depends |

0.05 - 0.3 |

- |

- |

\(\theta_{M G}\) |

Marine growth model |

1 |

0.2 - 0.5 |

\(W\) |

0.9 |

\(C_{D}\) |

Drag force coefficient |

0.6 - 1.3 |

0.2 - 0.3 |

\(L\) |

0.9 |

\(C_{M}\) |

Inertia force coefficient |

1.6 - 2.5 |

0.10 - 0.15 |

\(L\) |

0.9 |

\(p_{1}\) |

Horizontal pressure on wall |

0.90 |

0.20 |

\(L\) |

- |

Moment due to horizontal |

0.81 |

0.37 |

\(L\) |

- |

|

\(p_{4}\) |

Uplift pressure |

0.77 |

0.20 |

\(L\) |

- |

Moment due to uplift pressure |

0.72 |

0.34 |

\(L\) |

- |

\(\theta_{X}=\) model uncertainty of \(X, \rho_{i j}=\) correlation between members, \(N=\) normal, \(L=\) lognormal, \(E=\) exponential, \(W=\) Weibull, \(G=\) Gumbel

There is no generally valid one-to-one relationship between the visual wave height and the significant wave height (instrumentally measured), or between the visual wave period and zero-crossing wave period (instrumentally measured). Thus, usually correction factors should be applied to the visual observations, see for example [19.032].

The Global Wave Statistics (GWS) visual observations of wave climate, see [19.033], represent the only truly global set of wave data with a sufficiently long observation history to give reliable global climatic statistics. [19.033] states that it should not be necessary to apply any correction factors, usually used for estimating wave height and wave period from visual observations. However, the accuracy of the data is still questioned in the literature. The GWS data should be used with care, and if possible they should be checked against available instrumental or hindcast data for considered areas. For the North Pacific, the visual wave observations owing to [19.034] are probably of higher accuracy than the Global Wave Statistics data. The Global Wave Statistics data were collected from ships whose density of traffic in the North Pacific area was rather low.

The World Meteorological Organisation’s accuracy requirements for waves, in terms of \(95 \%\) confidence interval limits, are [19.035]: \(\pm 20 \%\) for significant wave height and \(\pm 1.0 ~s\) for the average wave period. However, the accuracy of the actual wave data may be widely varying and is very much related to the observation mode.

The instrumental accuracy depends on the type of instrument used. A study by [19.036] shows that properly calibrated instruments are in general equally accurate. Wave buoys are regarded as being highly accurate instruments, and error in the estimated significant wave height due to imperfections of the wave buoys may be considered as negligible for most sea states, [19.037], [19.038]. During the severe sea conditions, the buoy may be drawn through the crest of wave, causing a smoothing effect in the recorded data. In the presence of a strong surface current, the buoy will most likely underestimate high wave heights. External forces on the buoy (e.g., breaking waves, mooring) may cause violent accelerations, that will lead to overestimation of the waves. These uncertainties are difficult to quantify.

In steep waves, the differences between sea surface oscillations recorded by a fixed (Eulerian) probe or laser, and those obtained by a free-floating (Lagrangian) buoy can be very marked. Reference is made to, Vartdal et al. (1989), [19.039]. Thus the wave buoy data should not be used for estimation of wave profiles in steep waves.

Platform mounted wave gages and other wave sensing devices have the advantage that they measure directly sea surface displacement rather than the acceleration as the buoys. For accuracy of the platform data see e.g. [19.040].

Several investigations carried out in the last years indicate very promising results that support use of the satellite data. [19.041] demonstrated that over the range of wave heights 1m - 8m satellite altimeter derived significant wave heights were nearly as accurate as the ones obtained from surface buoy measurements. [19.042] have shown that the satellite data are suitable for analysing ocean areas dominated by large storms or monsoon flows (accuracy: \(COV=10 \%\) ).

Modelled wave data are produced operationally by major national meteorological services and are filed by the data centers. The accuracy of these data may vary and depends strongly on the hindcast models applied to generate the data as well as the adopted wind field. To allow hindcast data to be used, the underlying hindcast models must be calibrated with measured data.

As noted above neither measurements nor wave models can be entirely relied upon to provide unbiased and error-free estimates under all conditions. The best way of providing a reliable metocean database is to make use of both measurements and model data, and to quantify uncertainties related to them. Generally, the offshore industry regards the instrumentally measured data always superior to model derived data, and recommends to use them for evaluating the design and operational criteria. Note that for instrumentally recorded wave data sampling variability due to a limited registration time constitutes a significant part of the random errors.

For the JONSWAP and Pierson-Moskowitz spectrum the sampling variability coefficient of variation of the significant wave height and zero-crossing wave period are approximately \(4-6 \%\) and \(1.5-2.5 \%\) respectively.

An unbiased noise in the measurement system will increase the measured \(H_{S}\). This sampling variability leads to extrapolations of extreme wave heights and periods that are biased. A review of data from 17 storms at Forties carried out by [19.043] indicates that the storm-peak significant wave heights determined from a single 17 -minute record every three hours are biased by about \(6 \%\), relative to threehour-average values.

Long-term Description

The following epistemic uncertainties are related to the long-term description: data uncertainty (instrumental/hindcast/forecast errors, sampling variability due to limited registration time of sea states), statistical uncertainty (due to limited long-term sample, fitting technique applied) and modelling uncertainty (due to choice of the statistical model, the effects of clustering, climatic uncertainty, fitting technique). Experience shows that the long-term wave description is sensitive to almost all types of uncertainties, even though their relative contribution to the response/structure reliability analysis may be different for various applications and various response calculation procedures.

While both data uncertainty and statistical uncertainty is possible to quantify, and in some cases to eliminate, specification of model uncertainty is still difficult, especially as a theoretical basis for the probabilistic/deterministic models involved in the longterm description is most probably out of reach. However, it is possible to identify differences between predictions of different models, which can be used to give an idea of the model uncertainties involved. Lacking information, it is advisable to use information from various models in order to minimise the risk of wrong predictions, as suggested in [19.044].

The global approach utilising all data from long series of regular observations introduces correlation among observations (e.g. clustering), and may obscure critical tail behaviour. However, the method is less sensitive to uncertainties in the few largest data points. In the alternative Peak Over Threshold method extreme observations may be nearly independent, but their scarceness increases the statistical uncertainty relative to the global approach. The method is also more sensitive to errors in the few highest data points. There is no general agreement on whether the global approach or the event method should be used. A choice between the methods should depend on the data set at hand as well as the application considered. However, for fatigue calculations for steel or steel welds all data should generally be preferred. Further, for extreme value analysis there are reasons for favouring event models (Winterstein et al., 2001).

Sampling variability of measured wave data (due to registration time = 1024s and 3- hour spacing interval) will lead to a positive bias in long-term period extreme wave heights estimated either directly from measurements or from hindcast data calibrated with measurements, see [19.045]. Further, as shown by [19.046] the \(H_{s}\) distribution function is clearly negatively biased for storms with shorter duration and greater intervals between samples, and positively biased for storms with greater duration and more frequent samples. The bias in 100 -year Hs for 1-hour spacing and 3-hour spacing is not negligible. Furthermore, as demonstrated by [19.046], uncertainty in design criteria increases rapidly as the data record length decreases below that which is required to achieve an acceptable COV of, say, 0.1 . Too short record has to be compensated by adopting more expensive safety margins by a designer. Thus it may be more desirable to have record with some uncertainty in the accuracy of the data than to have a very short data record of perfect accuracy.

Climatic uncertainty appears when the observed data are obtained from a time interval that is not fully representative for the long-term variations of the environmental conditions. This may result in overestimation or underestimation of the design/operational wave. The database needs to cover at least 20 years of preferably 30 years or more in order to account for climatic variability. In regions where the predominating storm type is a hurricane, and the frequency of occurrence of extreme hurricanes at a site is low (such as in the Gulf of Mexico), the uncertainty in the 100year wave height might not reach a “comfortable” level until the data base coverage actually approaches 100 years, see [19.045].

In establishing very large data bases of wave data, there is the danger of joining in a sample data from different populations. [19.09] examined the case of single peaked sea states being pooled with combined ones, while [19.047] looked at the seasonal variability of the data and [19.048] studied the yearly variability of the data. The latter showed that the application of strict statistical criteria defining samples and population would not support pooling together data from different years. In fact, an explanation model was developed based on the concept of sampling from random populations.

There is no industry consensus on how to apply directional criteria in design. Usually the length of the data record is too short to provide a proper directional description of waves. Therefore directional criteria exist only for a few discrete, large directional sectors and they use to be biased. As recommended by [19.049], directional effects need to be included in the reliability analysis with some care. A recent directional model is published by [19.050].

Further studies quantifying relative importance of different types of uncertainties for short-term and long-term wave prediction are also called for.

Wave models

All uncertainties related to wave models should where possible be quantified and accounted for when specifying design and operational conditions. The numbers depend on type of application and circumstances.

Wave loads

The values of the coefficients \(C_{M}\) and \(C_{D}\) are a source of model uncertainty. For common structural cross sections, typical values of \(C_{D}\) are found in the range between 0.6 and 1.3. Similarly, typical values of \(C_{M}\) are found in the range between 1.6 to 2.5 .

The drag coefficient \(C_{D}\) is a function of Reynolds number. The inertia coefficient \(C_{M}\) can in many cases be evaluated theoretically, as the inertia force is essentially the same force as that evaluated by integrating the pressure over the cylinder surface in a velocity potential representation. Different values of the drag coefficient \(C_{D}\) and the inertia coefficient \(C_{M}\) below and above sea water level should be considered because of marine growth.

In the reliability analysis it is recommended to adopt \(C_{M}\) as a lognormally distributed variable with \(C O V=0.10\), and \(C_{D}\) as a lognormally distributed variable with \(C O V=0.20-0.30\), [19.051], [19.052].

The model uncertainties of the Goda formula (last four lines) have been studied by [19.053].

References

J.D. Wheeler. Method for calculating forces produced by irregular waves. In Proceedings 1st Offshore Technology Conference, OTC 1006. Houston, 1969.

W.J. Pierson and L. Moskowitz. A proposed spectral form for fully developed wind seas based on similarity theory of s.a. kitaigorodskii. J. Geoph. Res., 69:5181–5190, 1964.

Proceedings of International Ship Structures Congress, Delft, the Netherlands, July 20-24 1964.

M. Prevosto, H.E. Krogstad, S.F. Barstow, and C. Guedes Soares. Observations of the high-frequency range of the wave spectrum. J. Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, 1996.

J. A. Battjes. Engineering aspects of ocean waves and currents. In Seminar on Safety of Structures under Dynamic Loading. Trondheim, Norway, 1978.

E.M. Bitner-Gregersen and S. Haver. Joint environmental model for reliability calculations. In Proc. of the 1st International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference. Edinburgh, United Kingdom, August 11-15 1991.

S.S. Strekalov and S. Massel. On the spectral analysis of wind waves. Arch. Hydrot., 18:457–485, 1971.

M.K. Ochi and E.N. Hubble. On six-parameters wave spectra. In Proc. 15th Coastal Eng. Conf., volume 1, 301–328. 1976.

C. Guedes Soares and M.C. Nolasco. Spectral modelling of sea states with multiple wave systems. Journal of Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, 114:278–284, 1992.

M.S. Longuet-Higgins. The effects of non-linearities on statistical distributions in the theory of sea waves. J. Fluid Mech., 1963.

M.S. Longuet-Higgins. On statistical distribution of the heights of sea waves. J. Marine res., 11:245–266, 1952.

D.E. Cartwright and M.S. Longuet-Higgins. The statistical distribution of maxima of a random process. Proc. Roy. Soc. London, Ser.A, 1956.

M.S. Longuet-Higgins. On the distribution of heights of sea waves: some effects of non-linearities and finite band width. Journal of Geophysical Research, 85(C3):1519–1523, 1980.

S. Massel. Ocean Waves in the Coastal Zone. Elsevier, 1989.

A. Cavanie, M. Arhan, and R. Ezraty. A statistical relationship between individual heights and periods of storm waves. In Behaviour of Offshore Structures (BOSS’ 76), The Norwegian Institute of Technology. 1976.

M. Arhan and R. Ezraty. Statistical relations between successive wave heights. Acta Oceanologica, 1:151–158, 1978.

M.A. Tayfun. Distribution of crest-to-trough wave heights. J. Wtrway, Port, Coastal and Ocean Engng., 107(3):149–158, 1981.

M.A. Tayfun. Distribution of large wave heights. J. Wtrway, Port, Coastal and Ocean Engng., 116(6):686–707, 1990.

J. Skourup, N.-E. Ottesen Hansen, and K.K. Andreasen. Non-gaussian extreme waves in the central north sea. In Proc. of the 15th Int. Conf. on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, OMAE, volume I-Part A, 25–32. ASME, 1996.

A. Næss. Estimation of long return period design values for wind speeds. Journal of Engineering Mechanics, 124:252–259, 1998.

R.G. Prince-Wright. Maximum likelihood models of joint environmental data for tlp design. In Proc. of the 14th Int. Conf. on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering OMAE, volume 2. Copenhagen, Denmark, 1995. ASME.

A. Der Kiureghian and P.-L. Liu. Structural reliability under incomplete probability information. J. Eng. Mechanics, 113(8):1208–1225, 1986.

A. Næss. Technical note: on the long-term statistics of extremes. Applied Ocean Research, 6(4):227–228, 1984.

O. Ditlevsen. Stochastic model for joint wave and wind loads on offshore structures. Structural Safety, 24:139–163, 2002.

L.E. Borgman. Spectral density of ocean wave forces. In Journal ASCE, Waterways and Harbors Div.; Proceedings, ASCE Specialty Cong. on Coastal Engineering. Santa Barbara, CA, 1965. October 1965.

Y. Goda. Random seas and design of maritime structures. University of Tokyo press, Tokyo, 1985.

M. Kac and A.J.F. Siegert. On the theory of noise in radio receivers with square law detectors. Journal of Applied Physics, pages 383–400, 1947.

S.R. Winterstein, E.M. Bitner-Gregersen, and K.O. Ronold. Statistical and physical models of nonlinear random waves. In Proc. of the 10th Int. Conf. on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, volume II, 23–32. 1991.

A. Næss. The joint crossing frequency of stochastic processes and its application to wave theory. Journal of Applied Ocean Research, 1985.

S. Mizoguchi and K. Tanizawa. Impact wave loads due to slamming. Ship Technology Research, 43:139–154, 1996.

E.M. Bitner-Gregersen and Ø. Hagen. Uncertainties in data for the offshore environment. Structural Safety, 7:11–34, 1990.

N. Hogben, L.F. Da Cunha, and H.N. Oliver. Global Wave Statistics. Unwin Brothers Limited, London, England, 1986.

I. Watanabe and others. Winds and waves of the north pacific ocean 1974-1988. Papers of Ship Research Institute, 1992.

World Meteorological Organization. Guide to Meteorological Instruments and Methods of Observation. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 1983.

K. Hasselman and others. Measurements of wind-wave growth and swell decay during the joint north sea wave project (jonswap). Technical Report 12, Deutschen Hydrographischen Institut, Hamburg, Germany, 1973.

K. Steel and M.D. Earle. The status of data produced by ndbc wave data analyzer (wda) systems. In Proc. Ocean ’79, 212–220. 1979.

F. Monaldo. Expected differences between buoy and radar altimeter estimates of wind speed and significant wave height and their implication on buoy-altimeter comparisons. J. Geophys., pages 2285–2302, 1988.

T. Marthinsen and S.R. Winterstein. On the skewness of random surface waves. In Proc. of the 2nd International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference, 472–478. San Francisco, 1992. ISOPE.

C.J. Cardone, V.R. Shaw, and V.R. Swail. Uncertainties in metocean data. In Proceedings of the E&P Forum Workshop. 1995.

D.J.T. Carter, P.G. Challenor, and M.A. Srokosz. An assessment of geosat wave height and wind speed measurements. J. Geophys. Res., 1992.

C. Cooper and G.Z. Forristal. Title of the paper. In Proceedings of the 1995 Offshore Technology Conference. 1995.

W.D. Earle and L. Baer. Effects of uncertainties on extreme wave heights. J. Waterway, Port, Coastal and Ocean Division, 1982.

C. Guedes Soares. 1989.

J. Heideman, O.T. Gudmestad, and C. Petrauskas. Environmental conditions and forces for use in requalification of offshore structures. In Proceedings a Requalification of Offshore Structures Conference. USA, 1994.

J.C. Heideman, M. J. Santala, and R. Cuellar. Uncertainty and bias in metocean design criteria. In E&F FORUM Workshop. London, England, November 2/3 1995.

C. Guedes Soares and A. C. Henriques. Statistical uncertainty in long-term distributions of significant wave height. Journal of Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, 118:284–291, 1996.

C. Guedes Soares and J. A. Ferreira. Modelling long-term distributions of significant wave height. In C. Guedes Soares, editor, Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, 51–61. New York, 1995. ASME.

G. Z. Forristal and C. J. Shaw. Uncertainties in the design process. In Proceedings of the E&P Forum Workshop. 1995.

M.J. Sterndorff and J.D. Sørensen. A rational procedure for determination of directional individual design wave heights. In Proc. OMAE 2001 Conference. Rio de Janeiro, June 2001.

R.E. Haring and L.P. Spencer. Ocean test structure data base. In Proc., Intl. Conf. on Civ. Eng. in the Oceans IV, 669–683. ASCE, 1979.

R.G. Dean, Jen-Men Lo, and Johansson. Rare wave kinematics vs. design practice. In Proceedings, Civil Engineering in the Oceans 5, ASCE Specialty Conference. San Francisco, Cal., 1979.

J.W. Van der Meer, K. D'Angremond, and J. Juhl. Probabilistic calculations of wave forces on vertical structures. In Coastal Engineering 1994, 1754–1767. 1994.

Additional References

Arhan, M. and R. Ezraty (1978), “Statistical Relations Between Successive Wave Heights”, Acta Oceanologica, 1, 151-158.

Battjes, J. A. (1978), “Engineering Aspects of Ocean Waves and Currents”, Seminar on Safety of Structures under Dynamic Loading, Trondheim, Norway.

Belverova, D. (1994), “Wind Waves”, PhD, Polish Academy of Sciences, Gdansk.

Borgman, L.E. (1979), “Directional Wave Spectra from Wave Sensors”, Ocean Wave Climate, Plenum, New York, pp. 269-300

Buoy-altimeter Comparisons”, J. Geophys., pp. 2285-2302

Takahashi, S (1996): Design of vertical breakwaters. Port and Harbour Research Institute